Carving New Paths: An Interview with Rachel Meirs

Cofounder Aaron Harvey sat down with the artist to chat intrusive thoughts, creativity as a coping mechanism, and our OCD-inspired collab.

Written by Aaron Harvey

01 Rachel is a musician, printmaker and woodworker based in Brooklyn, New York.

02 After a dog attack in high school, Rachel developed an intense fear of dogs. She became overcome with anxiety around them, to the point it started interfering in her daily life.

03 She decided to perform a self-exposure by adopting a dog of her own. Since then, she's been able to work through her fear and live a balanced life.

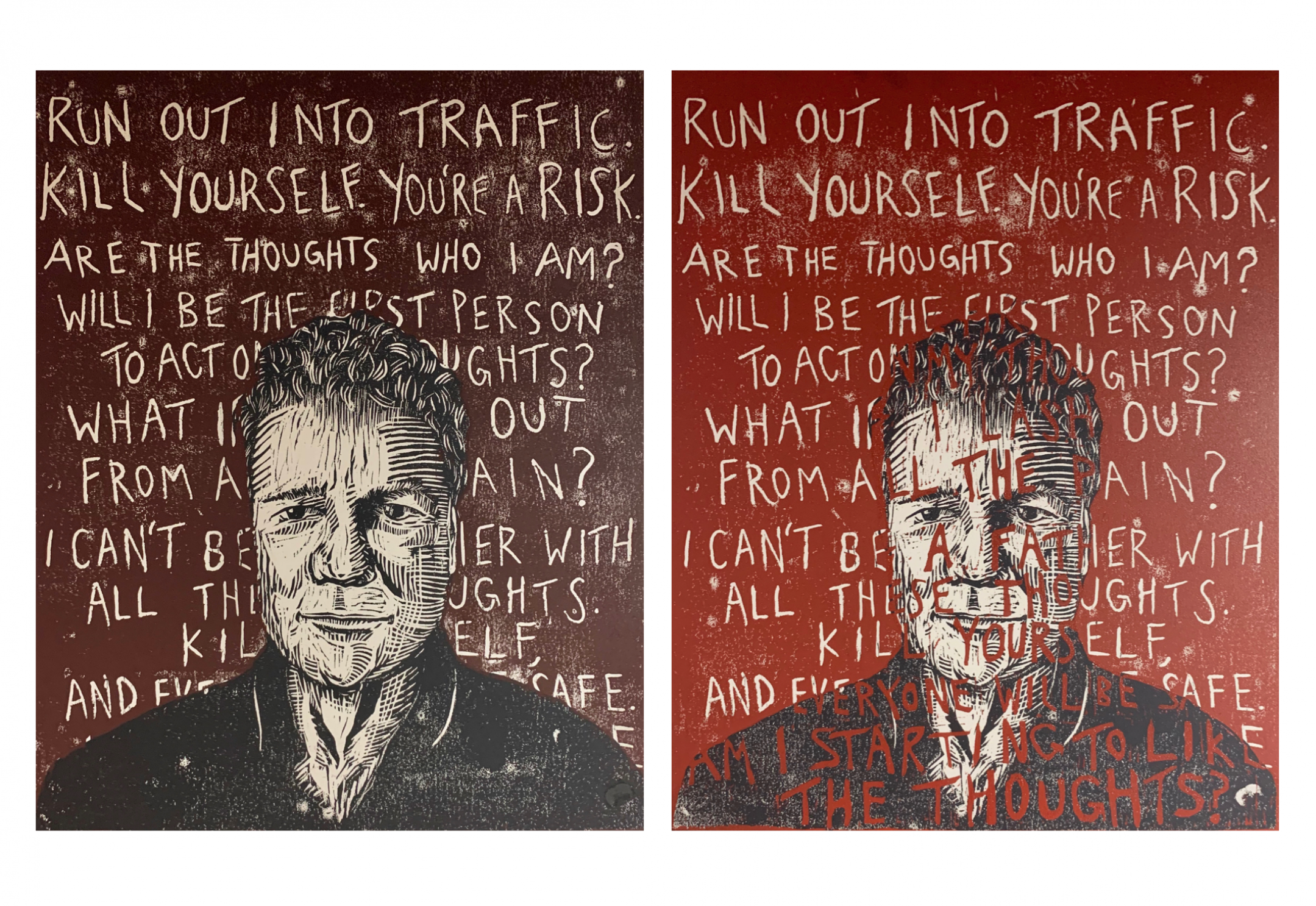

04 Pre-pandemic, we reached out to Rachel and asked her bring the intrusive thoughts of an OCD advocate, Scott Findlay, to life. These works will be displayed in an in-person exhibition in 2021.

Tell us a little bit about Rachel Meirs, the artist.

Well, I wouldn’t call myself an artist. But I do consider myself someone who loves to make things. And no matter what is going on in my life, or what line of work I’m in, art has always been the thing that’s the most fun.

That’s such an important distinction: forgetting the “identity” of being an artist, and focusing on the process of creation. How do you do it?

Truthfully, it’s not something I’ve mastered. You know, it can be so difficult just to accept the things you make without being destructively critical. I think my past experience as a classically trained musician taught me to be judgmental in extremes... it’s like you’re great, or you’re worthless, and there’s nothing in between. So nowadays, I really just try to enjoy the process of making things, and be less judgmental about the outcomes.

Ok, so tell us more about Rachel Meirs, the musician.

I just always assumed I would be a professional musician - I spent high school training really intensely, played in orchestras and chamber groups in the city on the weekends, spent my summers doing music intensives, it was really all I did. I was at the point of preparing for conservatory auditions my junior year and feeling confident about scholarship offers when I was attacked by a friend’s rottweiler.

I lost the use of my left hand and arm for over a year. Like, no functionality. It broke both bones, severed the tendons, and crushed my radial nerve - I’ve had several surgeries, two bone grafts, and a lot of physical therapy. So I had to accept that being a classical musician was no longer an identity I could claim.

Wow, I can’t imagine how hard that must have been. What’s your relationship with music now?

About three years after it happened, I started trying to learn how to play again. But you know, I physically couldn’t move my arm or hand the way I needed to play properly. I had to hold the viola differently. I was re-learning to play, but not able to do it as well - and that was actually the hardest thing, continuing to try despite knowing that I would never be as good as I was or wanted to be.

I think learning to accept that about music has also helped me take the pressure off of making art. When I’ve been rejected for a show, and I immediately start thinking, “I’m not a real artist… I didn’t deserve this anyway…”, I try to think… it’s OK. I have permission to enjoy what I’m doing and to keep doing it.

I love that idea... You don’t need validation to have permission to enjoy what you’re doing.

Exactly.

How has the trauma of the attack affected you?

Being around dogs was a major trigger for me. I was constantly imagining all the different ways I could be harmed. It started with dogs, then other animals, and people. Then, simple things like crossing the street became major triggers for me.

I’d picture all the cars driving into me. Or when I’m driving by a truck, I imagine it swerving into me, or a piece of lumber coming untied and coming in right through my windshield. You know, I’m just constantly imagining all of these different ways that I’m about to be in another horrific accident and playing the scenes in my head. I didn’t know they were called intrusive thoughts till I saw a therapist last year.

Have your intrusive thoughts led you to avoid things you’d otherwise want out of life?

For a long time my fear of dogs was so debilitating. And you don’t realize how many dogs you’re around every day until you’re terrified of them. I had moved from NYC to New Orleans, where there are houses and fenced in yards - every time I walked to the store, dogs would run up to the fence barking at me. I felt like I was having a heart attack every day.

It got to the point where I seriously felt like I couldn’t live anywhere there are houses with yards and dogs. And then I was like, well, that’s probably most places. So either I live with this incredibly inconvenient fear, or I find a way to make it less bad, and learn how to determine when I’m actually in danger and not just anxious.

So I adopted a dog. Her name is Frankie.

And you got a big dog, too.

Well she was only five pounds when I got her. The vet said she’d probably be about 30 pounds… She turned out to be 80 hah. So I’ve grown with her. I’ve learned how she interacts with other dogs. I see her negotiate the same things I do - are you nice? Should I be scared? is it okay?. And now I have someone to go through all of that with. She’s the best.

Yeah, super cool. Because you took that leap of faith with Frankie, it turned out to be a healthy form of exposure therapy for your PTSD.

Yea, I’ve realized that when a dog runs up to me, I can learn to stay calm, and accept that maybe this is OK. Maybe this will be OK. Maybe it’s fine.

Have you used mindfulness or anything else to help with the anxiety?

Not quite. But I think that just knowing there is a name for what I was experiencing, intrusive thoughts. Learning that. And knowing what it is allows me to anticipate it, recognize it as a thought, and just keep on walking.

What about making art? Is that a form of therapy for your anxiety?

Art is one of the few things that I do because I want to. I mostly work in woodcuts - the process is very physical. It’s very repetitive. You spend a lot of time drawing an image out. And then you spend a lot more time carving what you’ve already drawn into wood. And I love that. That’s my favorite part… just chipping away wood.

Before the pandemic, we started working on an art exhibition concept together. Tell us about that.

Yes, we were planning to tell the story of overcoming intrusive thoughts through a series of woodcuts. As part of the exhibition, we started creating woodcut portraits of advocates from the online community - people who have helped other people in the community find the support they need to move forward by being open with their own stories.

Right, specifically, Scott Findlay. He’s a sufferer who’s helped so many people around the world -- perfect strangers -- get the information they need to cope.

To bring Scott’s story to life, I wanted to carve his portrait in wood, and carve the words separately, to print one version with his intrusive thoughts running in the foreground, where they’re always present. And then to print another with the intrusive thoughts in the background to represent how you can move past, not let them overpower you, while accepting that they’re there and learning to live with them.

What got you excited about doing woodcuts to tell his story?

After our second brainstorming session for the exhibition, I got excited about how we would use woodcuts and printmaking to tell Scott’s story. And how it’s not arbitrary.

For example, the process of woodcutting allows you to create multiples. You can reduce and carve the same block multiple times, similar to what we experience with our thoughts. Woodcuts are also not perfect. They’re not designed to be. You have to accept that you can’t control every aspect of the wood carving process. Things will go wrong. And you have to accept the uncertainty of it all and find beauty in the imperfections.

And with woodcuts also, you know, they come from a tradition of being political. You know, it's printmaking, it's meant to be reproduced. It's not meant to be fine art, they can have a direct meaning, they should be accessible. Plywood is cheap. Art is for the people.

What advice would you give our readers who are really overwhelmed by their intrusive thoughts?

I don’t think DIY exposure therapy is the right move for everyone - but putting myself in situations that scared me (getting the dog, learning to use power tools, walking past a cow in close quarters, hah) are also situations in which I have been able to teach myself that not every move ends in disaster - and so when I’m struggling, and I want to lean into the idea that, this terrible thing happened one time! I can also remind myself, but it didn’t happen all these other times. I guess, just finding easy situations in which you can work yourself up to feeling brave, so that you have that experience when you face the hard ones.

What other projects are you working on that we should be on the lookout for in the coming months?

In addition to the work for this project, I’ve been making some more political woodcuts specifically as fundraiser pieces, working on a series of woodcuts about food and family, and right now I’m curating a project called Ziplock Zine (@ziplock.zine) which I’m super excited about - it’s been a way of encouraging other folks to make art and write, and I specifically made it as something that I wanted people who don’t identify as artists or writers to participate in - just encouraging anyone to make anything, reminding them they can, and that it can be shared, and maybe feel good.

In my not-art life, I’ve been working for an oral history project, and continuing my own research in occupational health, focusing on musicians’ healthcare access and the gig economy - now I’m figuring out how to adapt all that research to incorporate our covid world. That should keep me busy for a while.

Follow Rachel on Instagram at @rachel.meirs for woodcuts, printmaking and music.

Support our work

We’re on a mission to change how the world perceives mental health.