For Half Of Gen Z, Parents Stand In The Way Of Better Mental Health

How stigma can keep youth from accessing the resources they need.

Escrito por Kevin Singer

01 Kevin is the Head of Media and Public Relations at Springtide Research Institute.

02 He shares top findings from their newest report about mental health among Gen Z, and how educators can help.

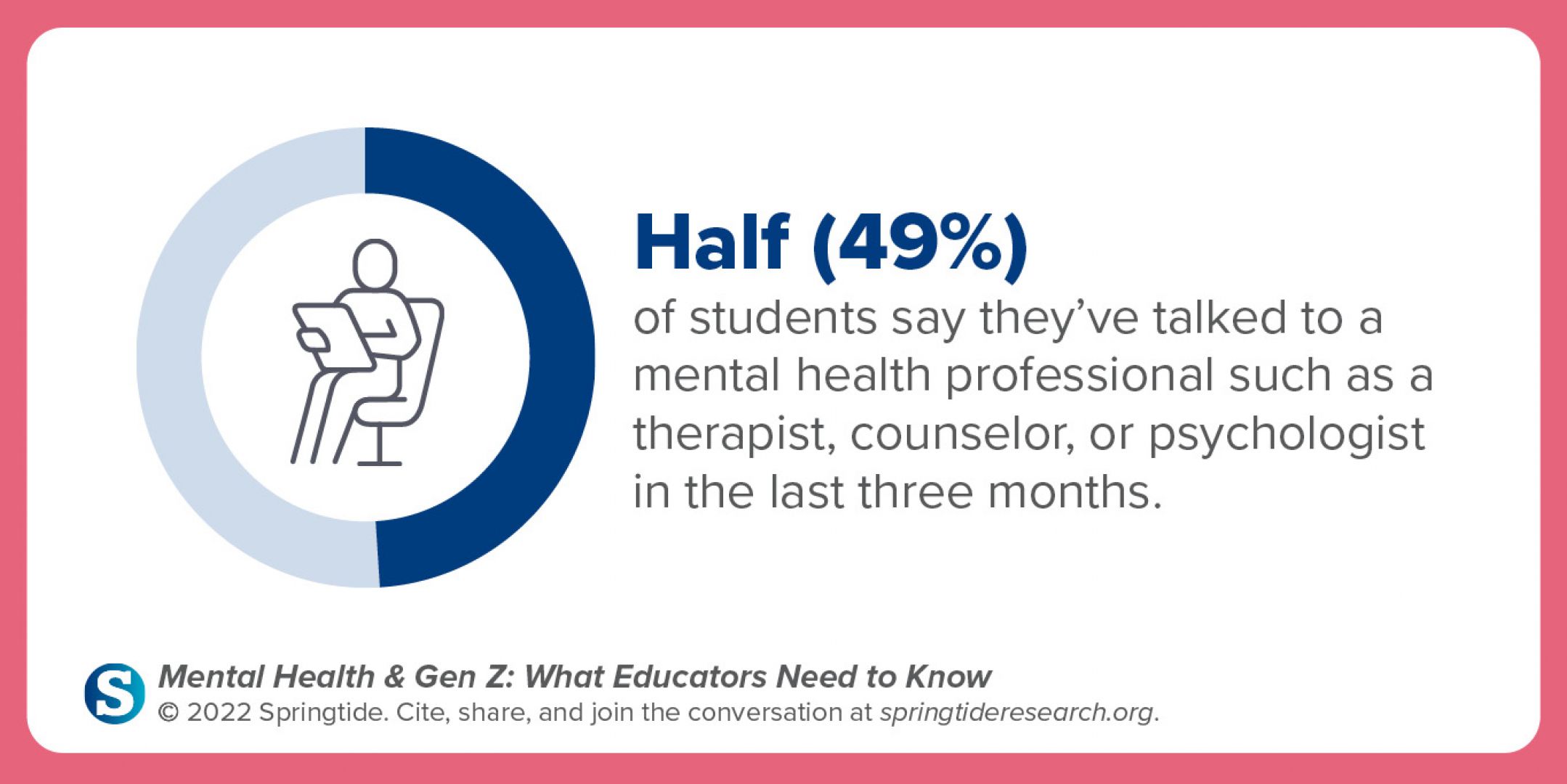

03 While half of Gen Z reported that they had recently talked to a mental health professional, their parents have yet to catch up on having open conversations about mental health.

Young people are struggling with their mental health at alarming rates, prompting the White House, the Surgeon General, and youth influencers like Selena Gomez and Lady Gaga to take action.

Springtide Research Institute, which recently performed a study on mental health in schools, discovered that half of 13-25 year old students (49%) have talked to a mental health professional such as a therapist, counselor, or psychologist in the last three months.

Experts are advocating for an all-hands-on-deck approach to confronting the issue, though many are placing special emphasis on the critical role of parents.

“There is an array of factors linked to anxiety and depression which parents can play an important role in mitigating,” Zara Mansoor, a Clinical Psychologist, wrote in The Conversation. “Supporting parents can have a positive preventative effect on the development of anxiety and depression.”

Yet, findings from Springtide’s mental health study found that for half of Gen Z students, they say their parents are serving as a barrier rather than a bridge to better mental health.

“They don’t take my mental health concerns seriously”

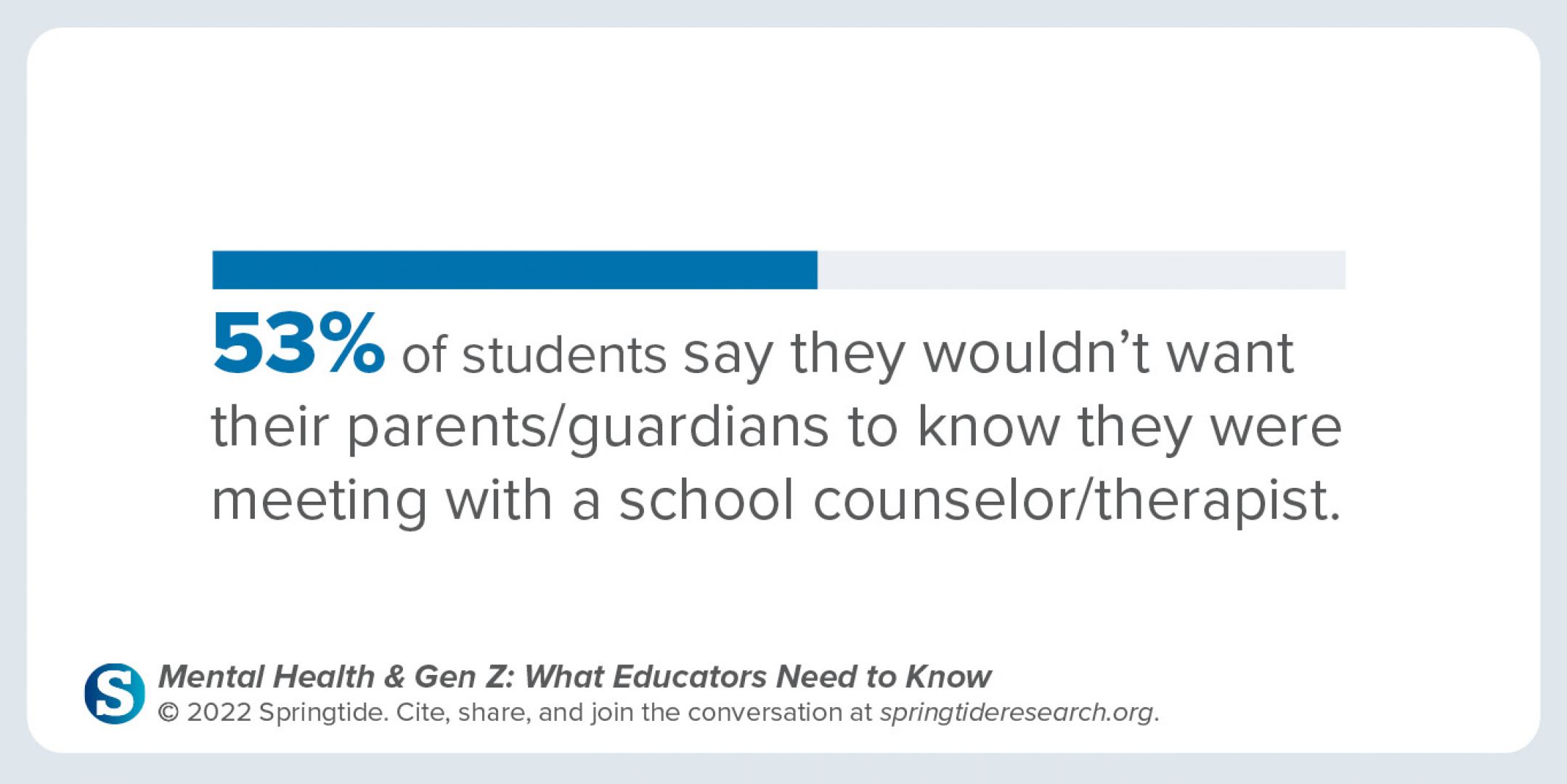

Springtide surveyed 3,139 students in middle school, high school, and college in Spring 2022, discovering that 49% agree, “My parents/guardians don’t take my mental health concerns seriously.” Even more students (53%) agree, “I wouldn’t want my parents/guardians to know I am meeting with a school counselor or therapist.”

Students from marginalized groups are even more likely to say their parents don’t take their mental health concerns seriously, such as LGB+ students (52%) compared to straight students (41%), Black students (53%) compared to White students (43%), nonbinary students (57%) compared to female-identifying (45%) and male-identifying (43%) students, and below-average income students (49%) compared to average or above-average income students (44%).

Why aren’t parents more effective in supporting their students’ mental health?

Mental health issues are “typically very hard for a teen to talk about with their parent or guardian,” Nicole Nadell, an assistant professor in pediatrics and psychiatry at Mount Sinai, told The New York Times.

For one, parents aren’t always sure whether the emotional struggles of their students are part of the typical moodiness associated with adolescence and growing up, or something more serious.

“If a child has a fever or a persistent cough, parents react — they pay attention and reach out for help. But if a child seems sad or irritable, or less interested in activities they used to enjoy, they tend to think of it as a phase, or teen angst, or something else that can be ignored,” Claire McCarthy of Harvard Medical School writes.

Parents are also prone to express frustration toward emotions they see as negative, rather than reading between the lines for what their students might be feeling underneath the surface.

"We look at kids who are irritable or angry, and we say they're bad or mad," Ken Ginsburg, a pediatrician and founder of the Center for Parent and Teen Communication, told Axios. "[But] that's how they show they're sad."

Condiciones relacionadas

The state of parenting and mental health

Research has shown that parenting style can make a big difference when it comes to the mental wellbeing of young adults. A parenting style that encourages understanding and acceptance of emotions is more effective than one that is dismissive or punitive.

But while many doctors see clear rationale for parents to be involved in their young adult’s mental health treatment, research into parental involvement in care is very limited.

In that vein, a slew of articles and resources offer similar tips for parents to be approachable, curious, nonjudgmental, good listeners, and sensitive to changes in behavior. In one recent study from the University of Michigan (UM), 95% of parents felt confident they would recognize a possible mental health issue in their adolescent. Yet, only one in four parents (25%) thought their adolescent would definitely talk with a parent about a possible mental health issue. Where’s the disconnect?

“Sometimes, the stigma of mental illness can make it hard for parents to seek help—even if they think their adolescent needs it,” write researchers at UM. “Parents might delay seeking care for their adolescent as they may think or hope the symptoms will go away on their own, be in denial, or think that mental illness cannot happen to their adolescent,” they add.

Just one-quarter of parents (27%) reported their adolescent has ever had a visit with a mental health specialist. However, some parents have trouble finding a mental healthcare evaluation or treatment options for their young adult. Nearly half (46%) described difficulties getting their adolescent care with a mental health specialist, including long waits for appointments (26%), finding a provider who took their insurance (15%) or saw children (13%), and knowing where to go (10%). “These difficulties highlight the strains in our current mental health system and point to the need for significant reform to support parents and their children,” the researchers conclude.

In lieu of access to formal mental health resources, UM researchers suggest that primary care doctor visits are a critical opportunity for parents to inquire about mental health issues. If they cannot be present at these appointments, they urge parents to “stress the importance of [their young adults] being honest with their provider about any physical or mental health problems and allow them privacy with their primary care physician.” For about 20% of parents, they were successful in securing mental health care for their young adult after receiving a referral from a primary care doctor.

Ending the stigma

A much bigger issue than proactive parents struggling to help their students, however, is that some parents may be perpetuating the stigma that seeking mental health support is a sign of weakness and in turn, discouraging young adults from seeking help.

Nearly half (45%) of students who participated in Springtide’s study, for example, say they hesitate to see a therapist because “I don’t think my parents take my mental health concerns seriously,” while a third of students (33%) agree, “My parents/guardians wouldn't want me to get help at school because they would be worried I might be treated differently or be given fewer opportunities.”

Parents can and must do more for the teens and college students in their lives. For some young adults, their lives literally depend on it. For helpful tips and ideas for promoting a mental-health friendly culture in your home, school, or organization, be sure to check out Springtide Research Institute’s new report, Mental Health & Gen Z: What Educators Need to Know.

<>

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Kevin Singer (@kevinsinger0) is Head of Media and Public Relations at Springtide Research Institute and a professor at two community colleges for the last ten years.

Apoya nuestro trabajo

Nuestra misión es cambiar la manera en que el mundo percibe la salud mental.